The wind is always having a turning effect on our sea kayaks. In this article we will look at why and what we can do to more easily control our boats in the wind. We will look at the physics of what is happening and then we will look at using this knowledge to make paddling in the wind easier.

We will look at this first while the boat is stationary, before going on to look at what is happening whilst the boat is being paddled. As with all good physics lessons it is based around experiments, that you can perform yourself. The experiments are best performed with an unloaded sea kayak, on flat water in a moderate breeze, about force 3-4 Beaufort should do nicely.

First of all let’s look at the physics of what happens whilst you are stationary in your boat. The best way to observe and understand this is to perform the following experiment. With your boat stationary and pointing into the wind, sit upright with your paddles out of the water and watch as the wind turns the boat. Allow it to do this until it stops turning.

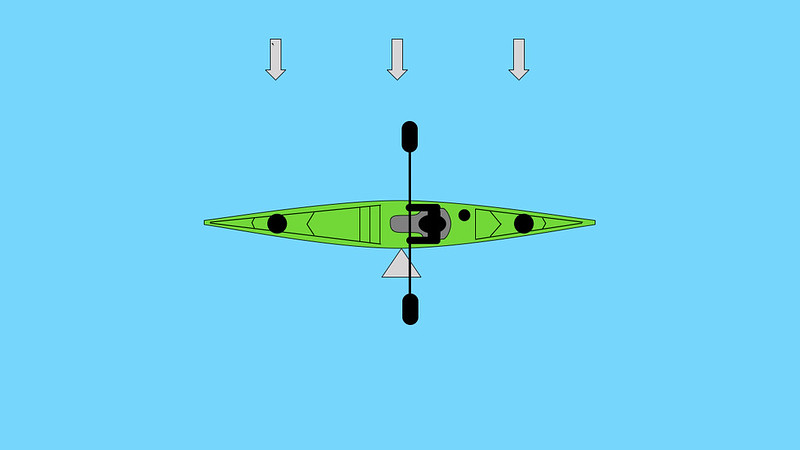

You should find that the boat stabilises its turning once it is roughly at right angles to the wind (the wind is represented by the grey arrows). To understand why we need to look at the pivot point (the pivot point is represented by the grey triangle). In this situation the pivot point is roughly in the middle of the boat as this is where your body weight is and the deepest part of the boat in the water, so the wind acts equally on the bow and stern of the boat turning it sideways on to the wind.

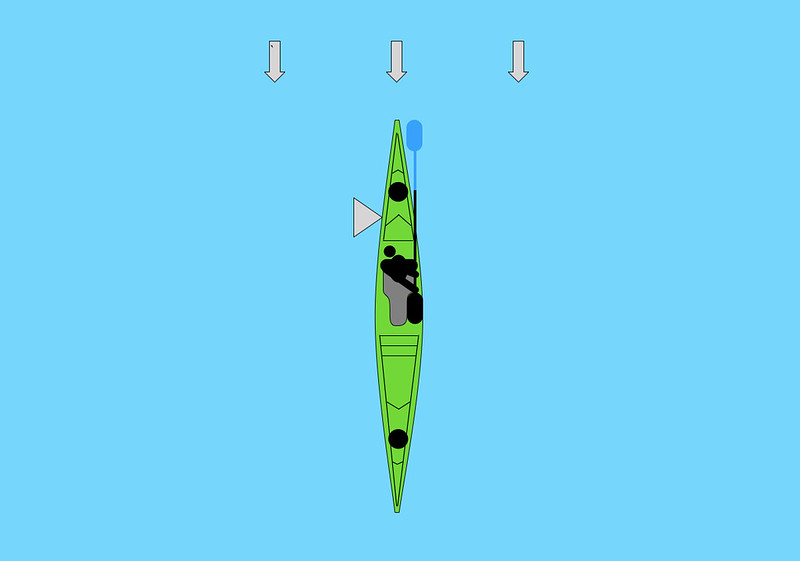

Then experiment with leaning back and putting the blade of the paddle in the water close to the stern of the boat.

By leaning back you move your bodyweight towards the back of the boat. This combined with sticking your blade in the water towards the back of the boat moves the pivot point backwards. This means there is more of the boat in front of the pivot point than behind it and so the wind blows the front of the boat downwind.

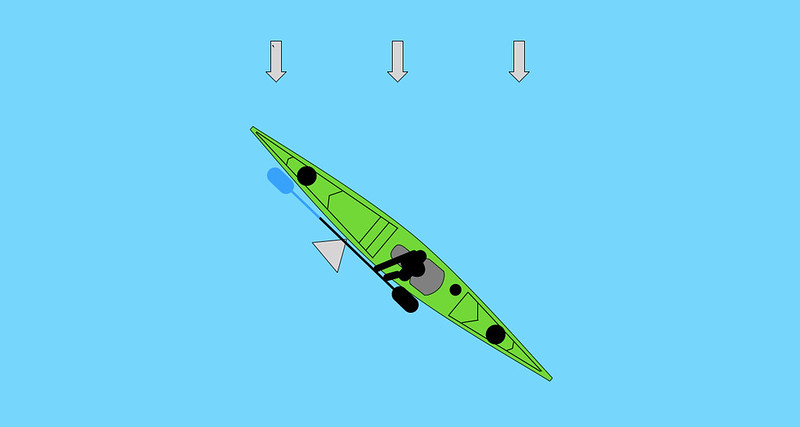

Then experiment with leaning forwards and putting the blade of your paddle in the water towards the bow of your kayak.

By leaning forwards you move your bodyweight towards the front of the boat. This combined with sticking your blade in the water towards the front of the boat moves the pivot point forwards. This means there is more of the boat behind the pivot point than in front of it and so the wind blows the back of the boat downwind. (You will probably notice that the boat doesn't turn up into the wind as much as it turned down wind in the previous experiment. There is a good reason for this that we will understand later.)

So how can we use this to help when we are trying to turn our kayak on the spot in windy conditions? Let’s keep it simple (but effective) and look at turning our kayak using forwards and reverse sweep strokes on alternating sides. As you’re turning your boat up into the wind you can lean forward and use your sweep strokes more towards the front of the boat. (i.e. start the forward sweep stroke with the blade at the bow of the boat and take it out around the mid point of the boat. And start the reverse sweep stroke around the mid point of the boat and push it all the way to the bow of the boat.) This moves the pivot point forward in the boat and lets the wind help you turn it. When turning your kayak down wind you can sit upright (leaning back makes you vunerable to capsizing) and use your strokes more towards the rear of the boat. This moves the pivot point backwards in the boat and again lets the wind help the turn.

Due to the design of sea kayaks (and there is a very good reason for this that again we shall understand later) it is harder to turn up into the wind and relatively easy to turn down wind. I find the best way to turn up into the wind is to use several really short forward sweep strokes right up at the front of the boat combined with the occasional reverse stroke that starts at the middle point of the boat and goes all the way to the front. Give it a go and see how many forward strokes you use in relation to each reverse stroke to get the best effect.

Now let’s look at the physics when you are paddling forward in your boat. Again the best way to observe and understand this is to perform the following experiment. Start by sitting still sideways on to the wind then start to paddle forwards but without steering your boat in any particular direction, let the boat go where it wants too. (As an experienced kayaker this can be quite difficult as you may steer subconsciously so if you need to you can look down at your spray deck to prevent yourself from steering) The faster you paddle the more noticeable the affect.

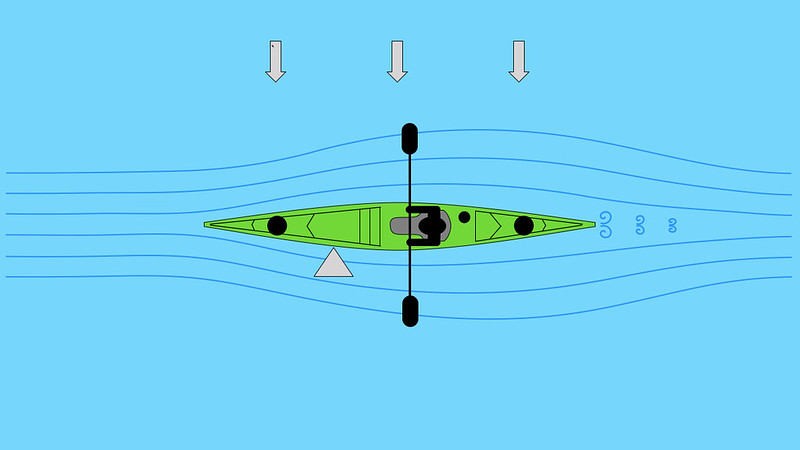

As you paddle forwards you should notice the boat turning up into the wind. This is because as the hull moves forward the bow pushes through the water creating a high pressure area around the front of the boat. This high pressure makes the water denser, or stickier at the front of the boat. The water filling in the space left behind the boat creates a low pressure area making the stern ‘looser’ in the water. These two factors have the effect of moving the pivot point of the boat forward and so the wind blows the stern of the boat down wind and the bow turns up into the wind.

This effect is called ‘weather cocking’ from the nautical terms of ‘weather’ meaning windward or upwind and ‘cocking’ meaning turning. It is an affect that happens to all displacement hulls from destroyers to dinghies. To help reinforce this idea, have a go at paddling backwards and you should find that your boat will turn backwards into the wind.

How can we use what we learnt from the experiments with a stationary boat to help reduce the weather cocking effect of a moving boat? Let’s look at paddling with the wind from the side first before looking at paddling into the wind and down wind.

We know from the previous experiment of paddling sideways on to the wind that when we paddle forwards we move the pivot point forwards and this causes the boat to turn upwind. Therefore if we lean slightly back (leaning back too far is poor forward paddling posture) and use our forward paddling strokes more towards the rear of the boat we will move the pivot point back and reduce the weather cocking effect. Also if we slow down we will reduce the high pressure at the bow and therefore reduce the weather cocking too.

Then lean forwards, use your forward paddling strokes more towards the front of the boat and speed up and you will increase the weather cocking effect.

With a bit of practice you will find that you can steer the boat quite significantly, into and away from the wind, simply by shifting your body weight and paddle stroke position forwards and backward, and by speeding up and slowing down.

When you want to paddle into the wind steering isn’t a problem as the weather cocking effect makes the boat turn into the wind. This is true up until the point when the wind becomes so strong that it slows the boat down enough to reduce the high pressure effect around the bow thus making the boat behave more like it is stationary. We know that a stationary boat will turn sideways on to the wind and so at this point you will need to lean forwards and use your paddle strokes more towards the front of the boat to help keep it pointing into the wind.

When paddling down wind, the pushing effect of the wind makes the boat move faster through the water and this increases the high and low pressure effect on the hull. This moves the pivot point of the boat even further forwards and the wind from behind keeps on pushing the stern off to one side or the other. To help reduce this effect you want to sit upright and use your paddle strokes more towards the rear of the boat. The easiest way to do this is to do a stern rudder at the end of a forward paddle stroke as and when you need too. Also slowing down reduces the weather cocking effect significantly.

So why not design a boat that doesn’t weather cock? Unfortunately it isn’t that easy. The main factor on how a boat behaves in the wind is the seat position of the boat as this determines where both the paddler’s weight and the paddle strokes will be. If designer puts the seat further back the boat weather cocks less but is harder to turn into the wind. To make it easier to turn into the wind the designer can move the sea forwards but the boat will then weather cock more.

If you look at the seating position in most sea kayaks you will notice that it puts the paddler’s weight slightly behind the centre of the boat. This is to reduce the weather cocking effect a little, without making the boat too hard to turn up into the wind.

But not all sea kayakers are the same shape. Let’s take two paddlers of the same weight who paddle the same boat model. Paddler 1 is slimmer with long legs while Paddler 2 is broader with short legs. When they are sitting in their sea kayaks Paddler 1 will have more body weight forward in the boat due to their long legs which weigh less relative to their slim upper body. Paddler 2 will have more body weight rearwards in the boat due to their short legs which weigh less relative their broad upper body. Therefore Paddler 1 will need to move their seat backwards, or put more kit in the rear hatches to prevent their boat weather cocking too much. Paddler 2 will need to move their seat forwards or put more kit in the front hatch to make their boat easier to turn into the wind when stationary.

So what about you and your boat? Fortunately most modern sea kayaks have moveable seats and if yours doesn't you can always load the boat bow or stern heavy. As we have discussed earlier there is no perfect solution. The less you make a boat weather cock when moving forwards, the harder you make it to turn into the wind while stationary. You need to experiment, with your boat and kit, both while stationary and moving forwards, to find a compromise that works for you.

Acknoledgment: This is a rewrite of an article I originally published in Feb 2017 for issue 31 of the Ocean Paddler magazine titled Turning in the Wind. As Ocean Paddler is now discontinued I have published it here.

By Philip Clegg

With over two decades of working in the sea kayaking industry, Phil can be found on a daily basis coaching for Sea Kayaking Anglesey. That's when he's not expeditioning or playing in his sea kayak and putting kit to the test.